The

Lore of the Wildnerness:

Point Reyes National Seashore

A visual lecture performed at the Prelinger Library as a part of Place Talks: Season 2,May 2016

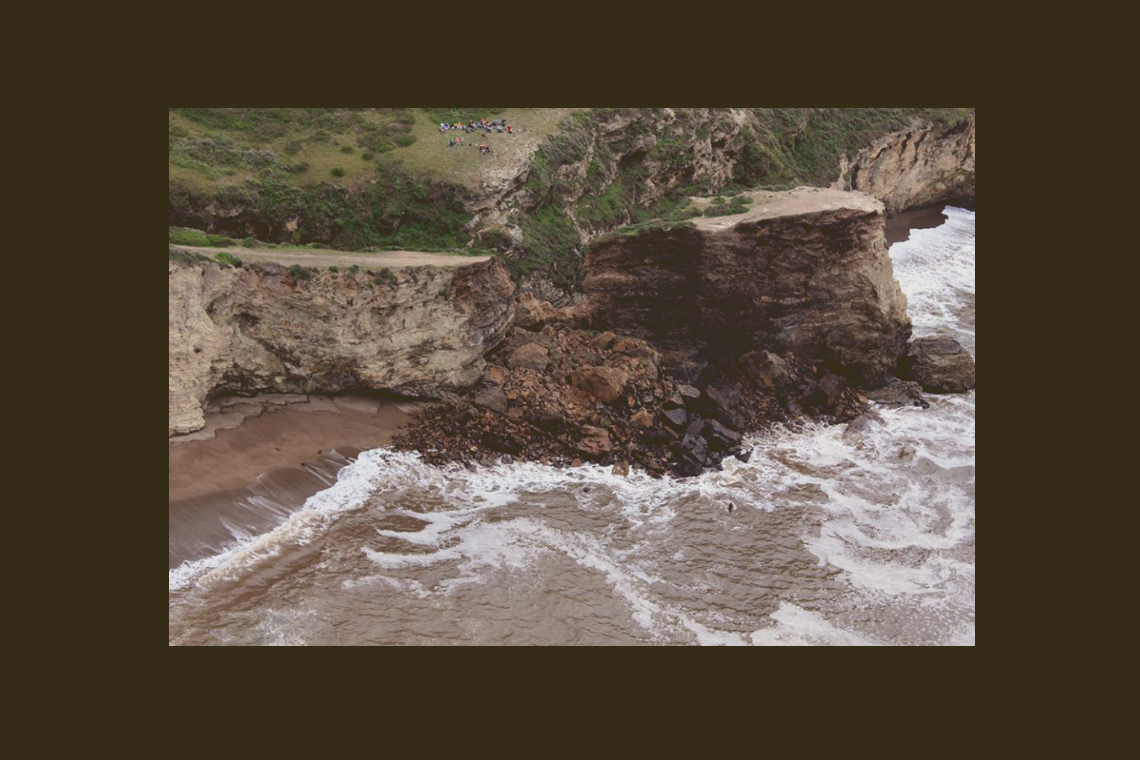

This is Arch Rock today

It used to be a main attraction in the park. A mild 4 mile hike from the main visitor center at Bear Valley that covers most types of terrain the park has to offer, including a nice meadow. Many of the park’s estimated 2.5 million annual visitors made this hike.

On March 21, 2015, the arch collapsed, tragically killing one hiker. Large fissures had developed a few days previous, but officials did not know how serious they were until the collapse. Many articles were published about the event, but none that I could find cite a specific reason for the collapse.

I can’t help but wonder if increased foot traffic to such a fragile landscape had any effect.

I knew the beach came to a point at its end, a small inlet leading to the swampy wet sands that lay over to the east of the dunes.

I could imagine it, a curved sandy beach, water surrounding, but I needed to see it for myself. I convinced her to walk with me, sold on the idea of adventure: experiencing a place for the first time.

As the dunes broke, their blades of grass holding small tufts of land above the wet sand, the wind picked up. Pushing against us, losing steps in the sand already, we meandered on, zig zagging through the dissipating dunes for breaks from the wind.

After dipping into Bass Lake so many times, I always wonder what this other lake would be like. How clear it would be, what might live in it. I notice the mouth, a break in the ridgeline. The water must pour out there, I think, down to the beach below.

I think about the sign for Crystal Lake we always pass before this, still wet from Bass Lake. A nearly overgrown trail that rises to the east between the two lakes. How pristine that place must be now. Signs warn of limited access, of rough trails, and protected habitats. Protected from us, a trust of preservation lost between the common man and they who do not answer.

As of 1860, there were an estimated 114 thousand people in the Bay Area.

There were 1.2 billion people in the world and 31 million in the US.

Land ownership in Point Reyes shifted in a major way as the US Land Commission began challenging the Mexican rancheros on the “validity” of their leases with the help of San Francisco lawyers. A battle which none of the rancheros won.

There were 1.2 billion people in the world and 31 million in the US.

Land ownership in Point Reyes shifted in a major way as the US Land Commission began challenging the Mexican rancheros on the “validity” of their leases with the help of San Francisco lawyers. A battle which none of the rancheros won.

Long, thick grass springs up against the edge of the trail along the marsh. Tiny brown bunnies often scurry across the trail, hopping from holes at the base of the grases, stopping in the middle of the trail to sneak a glance at you before they disappear. Deer just over the fence, cattle grazing in the small, stepped hills.

I think about the forests, the rocks, intimate ponds, the sculptured beaches, the vistas.

Perhaps it’s a feeling of home, belonging, recalling memories, that makes it hard to describe. Perhaps it’s the fear of impending separation and my inability to cope with the loss of place.

Bases are built, steel production and port industries boom in the Bay, and more people arrive in the wake.

Between 1950 and 1960, the Bay Area population raises from 1.7 million to 2.7 million.

22% of people in the Bay Area work in “Managerial/Professional” jobs.

Suburbia begins.

Between 1950 and 1960, the Bay Area population raises from 1.7 million to 2.7 million.

22% of people in the Bay Area work in “Managerial/Professional” jobs.

Suburbia begins.

In 1961, John F. Kennedy signed the legislation to help begin the nearly 15 years process of creating the park that would eventually become the protected Point Reyes National Seashore.

“Established in 1976, the Point Reyes wilderness has been constructed from a historic ranching landscape, and in the process of managing and interpreting this area, the history of its human habitation and use has been downplayed or overlooked. This erasure of history is not an accident; it represents a strategic reconfiguration of the landscape to bring it closer in appearance to public and agency expectations of what a wilderness area “ought” to look like.”

Laura Watt, The Trouble with Preservation, or, Getting Back to the Wrong Term for Wilderness Protection: A Case Study at Point Reyes National Seashore, 2002

“Established in 1976, the Point Reyes wilderness has been constructed from a historic ranching landscape, and in the process of managing and interpreting this area, the history of its human habitation and use has been downplayed or overlooked. This erasure of history is not an accident; it represents a strategic reconfiguration of the landscape to bring it closer in appearance to public and agency expectations of what a wilderness area “ought” to look like.”

Laura Watt, The Trouble with Preservation, or, Getting Back to the Wrong Term for Wilderness Protection: A Case Study at Point Reyes National Seashore, 2002

I often feel conflicted on a trail about where to go next.

I’ve made a route, a plan, talked about it with whomever I’m with. But I can’t help but feel something calling me, a certain direction or unknown point in the distance pulling at me. The ideas of what I might see there, experience there, race in mind: would it better? Have I made the right choices? Will I see the sunset?

Here, in this clearing, the sun blaring down on us, I wanted to go right, towards the water all of the sudden.

This is what Arch Rock probably looked like in the late 90s.

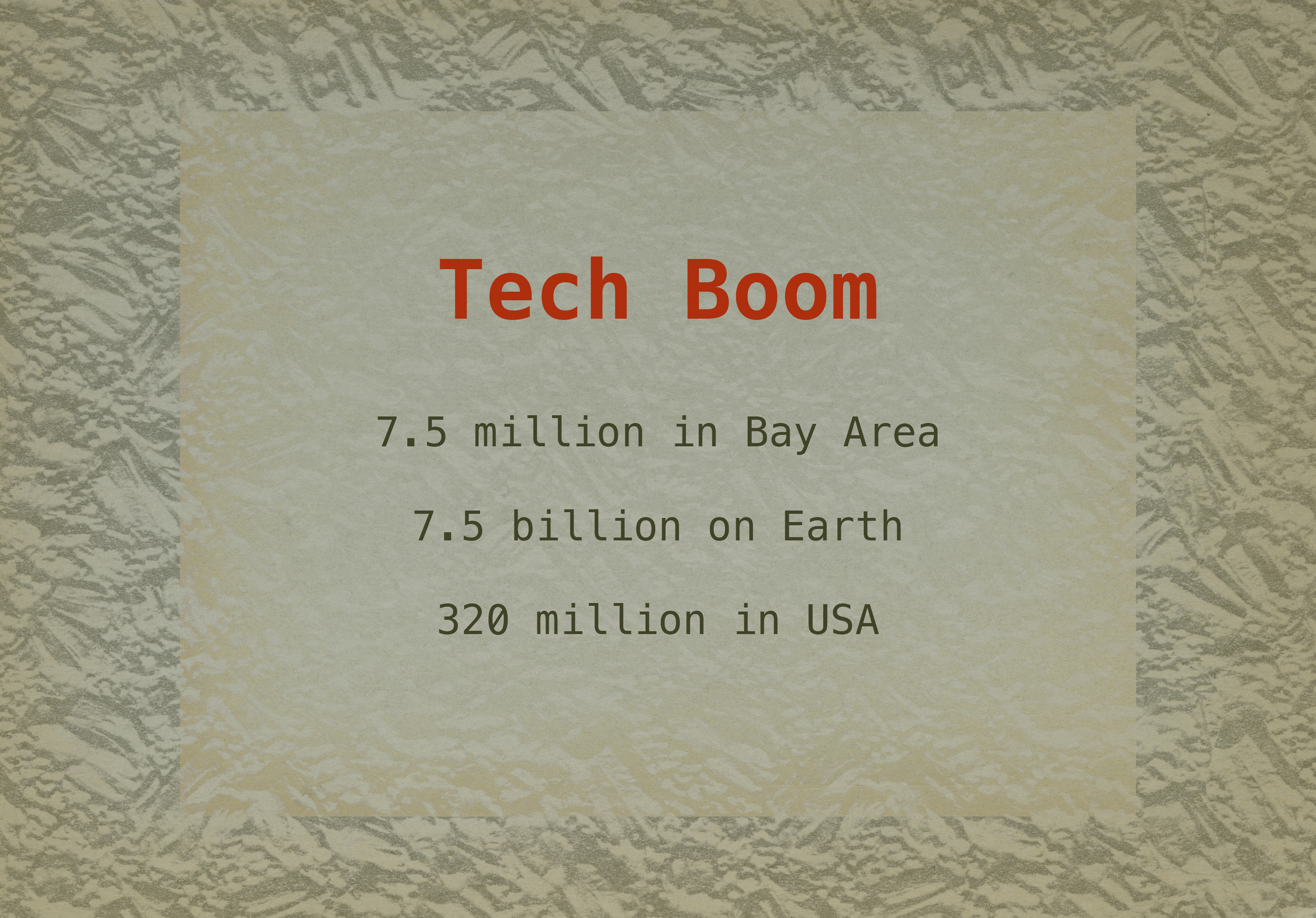

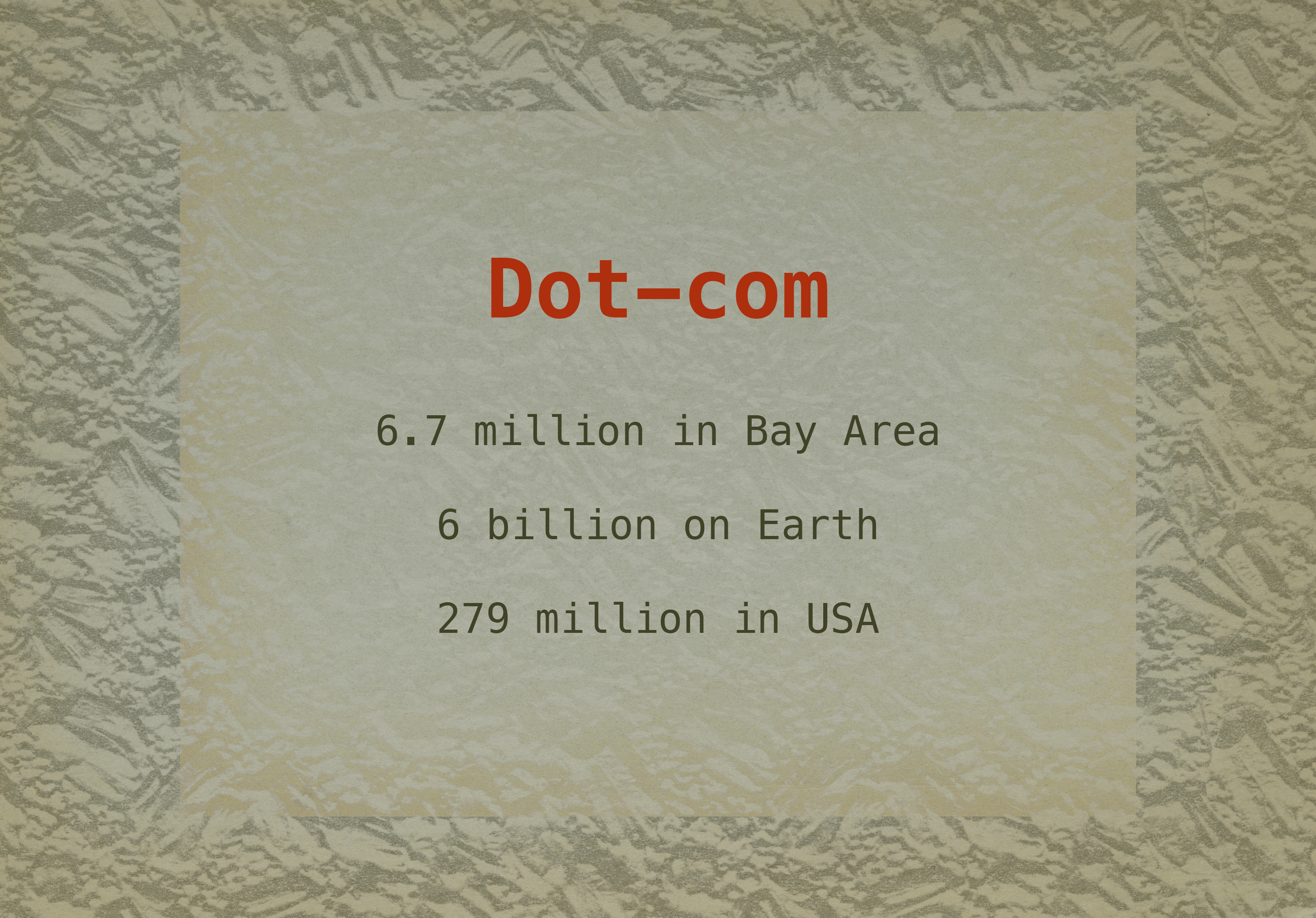

The .com boom was ablaze.

The .com boom was ablaze.

There were 6 billion people on the planet. 279 million of them were in the US. And 6.7 million lived in the Bay Area.

45% of which work in “Managerial/Professional” jobs.

Could you imagine if the Land Use Survey’s projection of 12 million people here would have been right?

45% of which work in “Managerial/Professional” jobs.

Could you imagine if the Land Use Survey’s projection of 12 million people here would have been right?

Once we sat under the stars, next to the smaller falls just above beach, where we had watched the sun go down.

We talked for a while, stirred around in the dirt a bit, until we heard a rustling across the way. Our headlamps reflected a set of eyes in the distant brush. We sat still, the eyes disappeared with a scuffle. Not knowingly exactly what it was, we took it as a sign to gather our things and head up the trail.